Students: Ross Middleton, Peter Russell, Mariana Gouveia, Kum-Tak Wong, Leroy Thompson.

From the Brief:

“Scope:

“No matter how good its offering, merchandising, or customer service, every retail company still has to contend with three critical elements of success: location, location, and location” (Taneja, 1999, p.136).

What is location? Why does it matter? A simple and intuitive answer is: centrality. A central place has one special feature to offer to those who live or work in a city: easy accessibility from immediate surroundings and more distant places. Accessibility may be transformed to visibility and popularity. Therefore, a central place tends to attract more customers and has a greater potential to develop into a social catalyst. Important landmarks such as museums, theatres or office headquarters favour the central locations. A more central location commands a higher real estate value and is occupied by a more intensive land use. Central locations in an urban area have the potential to sustain higher densities of retails and services, and are a key factor for supporting the formation and vitality of urban “nodes” (Newman and Kenworthy, 1999). Centrality emerges as one of the most powerful determinants for urban planners and designers to understand how a city works and to decide where renovation and redevelopment need to be placed.

Centrality does not only affect how a city works today, but also plays an important role in shaping its growth. If one looks at where a city centre is located, it is most likely to sprout from the intersection of main routes, where some special configuration of the terrain or some particular layout of the river system (or water bodies in general) makes the place compulsory to pass through. That is one of the dominant theories that explain where a city begins. Then, departing from such central locations, the city grows up over time with gradual additions of dwellings, residents and activities: first along the main routes, then filling the in-between areas, and then developing streets that realize loops and points of return. As the structure becomes more complex, new central streets and places are formed and stimulate growth of residents and activities around them. This evolutionary process has been driving the formation of urban fabrics and the advancement of human civilization throughout most of the seven millenniums of city history.

Centrality appears to be somehow at the heart of that marvellous hidden order that supports the formation of “spontaneous” and organic cities (Jacobs, 1961; 1993). It is also a crucial issue in the contemporary debate on searching for more bottom-up and “natural” strategies of urban planning beyond the modernistic heritage. Centrality has been studied in many branches of urban research, especially in economic geography and regional analysis (Wilson, 2000) and transportation planning (Meyer and Miller, 2000; Goulias, 2002). In most cases, centrality has been dealt with as a means to measure the relationship between activities among places. In essence, this has led to an interpretation of centrality in an intuitive notion that a more central location is a place “closer” to all others.

In urban planning and design, centrality is the core issue addressed by space syntax, a methodology of spatial analysis, even though under notions of “visibility” and “integration” (Hillier and Hanson, 1984; Hillier, 1996). Space syntax has opened a whole new range of opportunities for urban designers to develop a deeper understanding of several structural properties of city spaces. The model has achieved significant successes in the practice of countless urban regeneration programmes in the UK and elsewhere, and helped urban planners and designers in making good decisions and reframing the debate on pivotal issues such as crime, self-surveillance, community building and renovation of large housing estates in the last two decades or so. Despite of these successes, urban designers often perceive space syntax as a quantitative threat to the creativity embedded in the art of city design, while on the other side researchers in spatial analysis and geo-computation often find it lacks rigorous expression and clear disciplinary references.

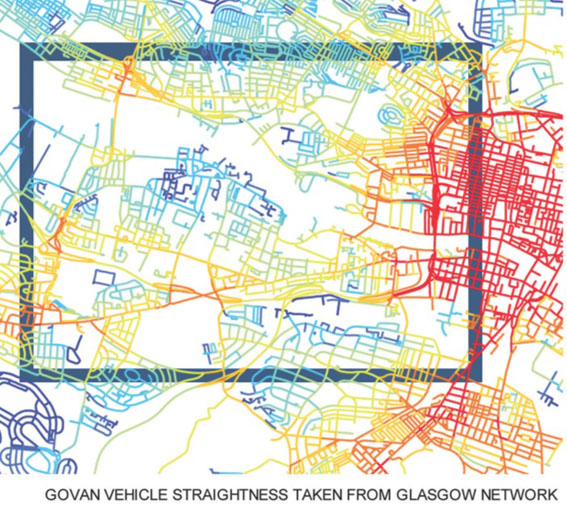

The Multiple Centrality Assessment (MCA) model follows broader traditions in centrality assessment, which draw back to structural sociology since the early 1950s (Bavelas, 1948, 1950; Freeman, 1977, 1979; also see an overview by Wasserman and Faust, 1994), and to the more recent new physics of complex networks (Boccaletti et al, 2006). Implementing these traditions in a spatial environment, MCA works on the forefront of a growing wave of interest for Geographic Information research (Batty, 2005). Therefore, the MCA model shares with space syntax the fundamental values that refer to the structural interpretation of urban spaces for urban planning and design, while offering a new and deeply alternative technical perspective (Porta et al, 2006a, 2006b; Cardillo et al, 2006; Crucitti et al, 2006a, 2006b; Scellato et al, 2006; Scheurer and Porta, 2006; Scheurer et al, 2007).

Objectives:

- To map the structural potential of each urban space in Govan to sustain a thriving and diverse local life, as expressed by its density of centrality with respect to all other places in the system.

- To test alternative scenarios of development of the street system in order to understand the impacts of local decisions on possibly remote spaces”.